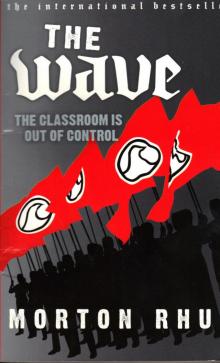

The Wave Read online

The Wave

Мортон Рю

THE WAVE IS SWEEPING THROUGH THE ENTIRE SCHOOL — AND IT IS OUT OF CONTROL...

It had begun as a simple history experiment to liven up their World War II studies, but, before long, Laurie Saunders sees her classmates change into chanting, saluting fanatics, caught up in a new organization called The Wave.

Laurie is afraid, but realizes that she must do something to stop it before it's too late...

A compelling novel based on a true incident that occurred in a high school history class in California.

Morton Rhue

The Wave

1

Laurie Saunders sat in the publications office at Gordon High School chewing on the end of a Bic pen. She was a pretty girl with short light-brown hair and an almost perpetual smile that only disappeared when she was upset or chewing on Bic pens. Lately she'd been chewing on a lot of pens. In fact, there wasn't a single pen or pencil in her pocket-book that wasn't worn down on the butt end from nervous gnawing. Still, it beat smoking.

Laurie looked around the small office, a room filled with desks, typewriters, and light tables. At that moment there should have been kids at each one of those type-writers, punching out stories for The Gordon Grapevine, the school paper. The art and layout staff should have been working at the light tables, laying out the next issue. But instead the room was empty except for Laurie. The problem was that it was a beautiful day outside.

Laurie felt the plastic tube of the pen crack. Her mother had warned her once that someday she would chew on a pen until it splintered and a long plastic shard would lodge in her throat and she would choke to death on it. Only her mother could have come up with that, Laurie thought with a sigh.

She looked up at the clock on the wall. Only a few minutes were left in the period anyway. There was no rule that said anyone had to work in the publications office during their free periods, but they all knew that the next edition of The Grapevine was due out next week. Couldn't they give up their Frisbees and cigarettes and suntans for just a few days in order to get an issue of the paper out on time?

Laurie put her pen back in her pocket-book and started to gather up her notebooks for the next period. It was hopeless. For the three years she'd been on the staff, The Grapevine had always been late. And now that she was the editor-in-chief it made no difference. The paper would be done when everyone got around to doing it.

Pulling the door of the publications office closed behind her, Laurie stepped out into the hall. It was practically empty now; the bell to change classes had not yet rung, and there were only a few students around. Laurie walked down a few doors, stopped outside a classroom, and peered through the window.

Inside, her best friend, Amy Smith, a petite girl with thick, curly, Goldilocks hair, was trying to endure the final moments of Mr Gabondi's French class. Laurie had taken French with Mr Gabondi the year before and it had been one of the most excruciatingly boring experiences of her life. Mr Gabondi was a short, dark, heavy-set man who always seemed to be sweating, even on the coldest winter days. When he taught, he spoke in a dull monotone that could easily put the brightest student to sleep, and even though the course he taught was not difficult, Laurie recalled how hard it had been to pay enough attention to get an A.

Now watching her friend struggle to stay interested, Laurie decided she needed some cheering up. So, positioning herself outside the door where Amy could see her but Gabondi could not, Laurie crossed her eyes and made an idiotic face. Amy reacted by putting her hand over her mouth to keep from laughing. Laurie made another face and Amy tried not to look, but she couldn't help turning back to see what her friend was doing next. Then Laurie did her famous fish face: she pushed her ears out, crossed her eyes, and puckered her lips. Amy was trying so hard not to laugh that tears started to roll down her cheeks.

Laurie knew she shouldn't make any more faces. Watching Amy was too funny — anything could make her laugh. If Laurie did any more, Amy would probably fall out of her seat and roll into the aisle between the desks. But Laurie couldn't resist. Turning her back to the door to create some suspense, she screwed up her mouth and eyes, and then spun around.

Standing at the door was a very angry Mr Gabondi. Behind him Amy and the rest of her class were in hysterics.

Laurie's jaw dropped. But before Gabondi could reprimand her, the bell rang and his class was suddenly spilling out into the hall around him. Amy came out holding her sides in pain from laughing so hard. As Mr Gabondi glared at them, the two girls went off arm in arm towards their next class, too out of breath to laugh any more.

In the classroom where he taught history, Ben Ross crouched over a film projector, trying to thread a film through the complex maze of rollers and lenses. This was his fourth attempt and he still hadn't got it right. Frustrated, Ben ran his fingers through his wavy brown hair. All his life he had been befuddled by machinery — film projectors, cars, even the self-service pump at the local garage drove him bananas.

He had never been able to figure out why he was so inept in that way, and so when it came to anything mechanical, he left it to Christy, his wife. She taught music and choir at Gordon High, and at home she was in charge of anything that required manual dexterity. She often joked that Ben couldn't even be trusted to change a light bulb correctly, although Ben insisted this was an exaggeration. He had changed a number of light bulbs in his life and could only recall breaking two in the process.

Thus far in his career at Gordon High — Ben and Christy had been teaching there for two years — he had managed to hide his mechanical inabilities. Or rather, they had been overshadowed by his growing reputation as an outstanding young teacher. Ben's students spoke of his intensity — the way he got so interested and involved in a topic that they couldn't help but be interested also. He was “contagious”, they'd say, meaning that he was charismatic. He could get through to them.

Ross's fellow faculty members were somewhat more divided in their feelings towards him. Some of them were impressed with his energy and dedication and creativity. It was said that he brought a new outlook to his classes, that, whenever possible, he tried to teach his students the practical, relevant aspects of history. If they were studying the political system, he would divide the class into political parties. If they studied a famous trial, he might assign one student to be the defendant, others to be the prosecution and defence lawyers, and still other to sit as the jury.

But other faculty members were more sceptical about Ben. Some said he was just young, naive, and over-zealous, that after a few years he would calm down and start conducting classes the “right” way — lots of reading, weekly quizzes, classroom lectures. Others simply said they didn't like the way he never wore a suit and tie in class. One or two might even admit they were just plain jealous.

But if there was one thing no teacher had to be jealous of, it was Ben's total inability to cope with film projectors. While perhaps brilliant otherwise, now he only scratched his head and looked at the tangle of celluloid bunched in the machine. In just a few minutes his senior history class would arrive, and he had been looking forward to showing them this film for weeks. Why hadn't his teacher's college given a course in film threading?

Ross rolled the film back into its spool and left it unthreaded. No doubt one of the kids in his class was some kind of audiovisual whiz and could get the machine going in an instant. He walked back to his desk and picked up a pile of homework papers he wanted to distribute to the students before they saw the film.

The marks on the papers had become predictable, Ben thought as he thumbed through them. As usual, there were two A papers, Laurie Saunders's and Amy Smith's.

There was one A—, then the normal bunch of B's and C's. There were two D's. One was Brian A

mmon, a quarterback on the football team, who seemed to enjoy getting low marks, even though it was obvious to Ben that he had the brains to do much better if he tried. The other D was Robert Billings, the class loser. Ross shook his head. The Billings boy was a real problem.

Outside in the hall the bells rang, and Ben heard the sounds of class doors banging open and students flooding into the corridors. It was peculiar how students always left class so quickly but somehow arrived at their next class at the speed of snails. Generally Ben believed that high school today was a better place for kids to learn than it was when he went. But there were a few things that bothered him. One was his students' lackadaisical attitude about getting to class on time. Sometimes five or even ten minutes of valuable class time would be lost while students straggled in. Back when he was a student, if you weren't in class when the second bell rang, you were in trouble.

The other problem was the homework. Kids just didn't feel compelled to do it any more. You could yell, threaten them with F's or detention, and it didn't matter. Homework had become practically optional. Or, as one of his ninth-graders had told him a few weeks before, “Sure I know homework is important, Mr Ross, but my social life comes first.”

Ben chuckled. Social life.

Students were starting to enter the classroom now. Ross spotted David Collins, a tall, good-looking boy who was a running back on the football team. He was also Laurie Saunders's boyfriend.

“David,” Ross said, “do you think you could get that film projector set up?”

“Sure thing,” David replied.

As Ross watched, David kneeled beside the projector and went to work nimbly. In just a few seconds he had it threaded. Ben smiled and thanked him.

Robert Billings trudged into the room. He was a heavy boy with shirt-tails perpetually hanging out and his hair always a mess, as if he never bothered to comb it after getting out of bed in the morning. “We gonna see a movie?” he asked when he saw the projector.

“No, dummy,” said a boy named Brad, who especially enjoyed tormenting him. “Mr Ross just likes to set up projectors for fun.”

“Okay, Brad,” Ben said sternly. “That's enough.”

A sufficient number of students had arrived for Ross to start handing out the homework papers. “All right,” he said loudly to get the class's attention. “Here are last week's papers. Generally speaking, you did a good job.” He walked up and down the aisles passing each paper to its author. “But I'm warning you again. These papers are getting much too sloppy.” He stopped and held one up for the class to see. “Look at this. Is it really necessary to doodle in the margins of a homework paper?”

The class tittered. “Whose is it?” someone asked.

“'None of your business.” Ben shuffled the papers in his hand and kept handing them out. “From now on, I'm going to start lowering grades on any papers that are really sloppy. If you've made a lot of changes or mistakes on a paper, make a new, neat copy before you hand it in. Got that?”

Some members of the class nodded. Others weren't even paying attention. Ben went to the front of the classroom and pulled down the movie screen. It was the third time that semester he'd talked to them about messy homework.

2

They were studying World War Two, and the film Ben Ross was showing his class that day was a documentary depicting the atrocities the Nazis committed in their concentration camps. In the darkened classroom the class stared at the movie screen. They saw emaciated men and women starved so severely that they appeared to be nothing more than skeletons covered with skin. People whose knee joints were the widest parts of their legs.

Ben had already seen this film or films like it half a dozen times. But the sight of such ruthless inhumane cruelty by the Nazis still horrified him and made him feel angry. As the film rolled on, he spoke emotionally to the class: “What you are watching took place in Germany between 1934 and 1945. It was the work of a man named Adolf Hitler, originally a menial labourer, porter, and house painter, who turned to politics after World War One. Germany had been defeated in that war, its leadership was at a low ebb, inflation was high, and thousands were homeless, hungry, and jobless.

“For Hitler it was an opportunity to rise quickly through the political ranks of the Nazi Party. He espoused the theory that the Jews were the destroyers of civilization and that the Germans were a superior race. Today we know that Hitler was a paranoid, a psychopath, literally a madman. In 1923 he was thrown in jail for his political activities, but by 1934 he and his party had seized control of the German government.”

Ben paused for a moment to let the students watch more of the film. They could see the gas chambers now, and the piles of bodies laid out like stove wood. The human skeletons still alive had the gruesome task of stacking the dead under the watching eyes of the Nazi soldiers. Ben felt his stomach churn.. How on God's earth could anyone make anyone else do something like that, he asked himself.

He told the students: “The death camps were what Hitler called his “Final solution to the Jewish problem”. But anyone — not just Jews — deemed by the Nazis as unfit for their superior race was sent there. They were herded into camps all over Eastern Europe, and once there they were worked, starved, and tortured, and when they couldn't work any more, they were exterminated in the gas chambers. Their remains were disposed of in ovens.” Ben paused for a moment and then added: “The life expectancy of the prisoners in the camps was two hundred and seventy days. But many did not survive a week.”

On the screen they could see the buildings that housed the ovens. Ben thought of telling the students that the smoke rising from the chimneys above the buildings was from burning human flesh. But he didn't. The experience of watching this film would be awful enough. Thank God man had not invented a way to convey smells through film, because the worst thing of all would have been the stench of it, the stench of the most heinous act ever committed in the history of the human race.

The film was ending and Ben told his students: “In all, the Nazis murdered more than ten million men, women, and children in their extermination camps.”

The film was over. A student near the door flicked the classroom lights on. As Ben looked around the room, most of the students looked stunned. Ben had not meant to shock them, but he'd known that the film would. Most of these students had grown up in the small, suburban community that spread out lazily around Gordon High. They were the products of stable, middle-class families, and despite the violence-saturated media that permeated society around them, they were surprisingly naive and sheltered. Even now a few of the students were starting to fool around. The misery and horror depicted in the film must have seemed to them like just another television programme. Robert Billings, sitting near the windows, was asleep with his head buried in his arms on his desk. But near the front of the room, Amy Smith appeared to be wiping a tear out of her eye. Laurie Saunders looked upset too.

“I know many of you are upset,” Ben told the class. “But I did not show you this film today just to get an emotional reaction from you. I want you to think about what you saw and what I told you. Does anyone have any questions?”

Amy Smith quickly raised her hand.

“Yes, Amy?”

“Were all the Germans Nazis?” she asked.

Ben shook his head. “No, as a matter of fact, less than ten per cent of the German population belonged to the Nazi Party.”

“Then why didn't anyone try to stop them?” Amy asked.

“I can't tell you for sure, Amy,” Ross told her. “I can only guess that they were scared. The Nazis might have been a minority, but they were a highly organized, armed, and dangerous minority. You have to remember that the rest of the German population was unorganized, and unarmed and frightened. They had also gone through a terrible period of inflation that had virtually ruined their country. Perhaps some of them hoped the Nazis would be able to restore their society. Anyway, after the war, the majority of Germans said they didn't know about the atrocities.�

�

Near the front of the room, a young black named Eric raised his hand urgently. “That's crazy,” he said. “How could you slaughter ten million people without somebody noticing?”

“Yeah,” said Brad, the boy who had picked on Robert Billings before class began. “That can't be true.”

It was obvious to Ben that the film had affected a large part of the class, and he was pleased. It was good to see them concerned about something. “Well,” he said to Eric and Brad, “I can only tell you that after the war the Germans claimed they knew nothing of the concentration camps or the killings.”

Now Laurie Saunders raised her hand. “But Eric's right,” she said. “How could the Germans sit back while the Nazis slaughtered people all around them and say they didn't know about it? How could they do that? How could they even say that?”

“All I can tell you,” Ben said, “is that the Nazis were highly organized and feared. The behaviour of the rest of the German population is a mystery — why they didn't try to stop it, how they could say they didn't know. We just don't know the answers.”

Eric's hand was up again. “All I can say is, I would never let such a small minority of people rule the majority.”

“Yeah,” said Brad. “I wouldn't let a couple of Nazis scare me into pretending I didn't see or hear anything.”

There were other hands raised with questions, but before Ben could call on anyone, the bell rang out and the class was rushing out into the hall.

David Collins stood up. His stomach was grumbling like mad. That morning he'd got up late and had to skip his usual three-course breakfast to make it to school on time. Even though the film Mr Ross had shown really bothered him, he couldn't help thinking that next period was lunch.

He looked over at Laurie Saunders, his girl friend, who was still sitting in her seat. “Come on, Laurie,” he urged her. “We have to get down to the cafeteria fast. You know how long the queue gets.”

The Wave

The Wave